Metropolis & the Mysteries: A Visual Analysis

Analyzing the esoteric and occult symbolism of Fritz Lang's magnum opus...

“Symbolism is the language of the Mysteries.

By symbols men have ever sought to communicate to each other those thoughts which transcend the limitations of language.”

— Manley P. Hall (33°), The Secret Teachings of All Ages

The Wolves Within is a must-read for every believer who refuses to be deceived.

Hit the Tip Jar and help spread the message!

This post contains affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission or affiliate fee for purchases made through these links.

Unlock the mysteries of Biblical cosmology and enrich your faith with some of the top rated Christian reads at BooksOnline.club.

Click the image below and be sure to use promo code SCIPIO for 10% off your order at HeavensHarvest.com: your one stop shop for emergency food, heirloom seeds and survival supplies.

Related Entries

The role of esoterica and occult symbology in mass communication has become both insidious and paramount in the modern era.

The prominent role which Hollywood has played in psychological and spiritual warfare during the 20th century bears oft repeating:

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA, reported that “the motion picture is one of the most powerful propaganda weapons at the disposal of the United States.” This declassified OSS report identified the ability for movies to stimulate or inhibit action, the ability to allay or aggravate anxiety, as well as the powerful ability to form attitudes and belief systems. The crucial part that cinema and television has had in the pantheon of psychological weaponry is impossible to overstate.

The colossal role that the US military and CIA has in Hollywood productions is a well established fact. From script rewrites to outright pro-war agitprop, the US Government has had generations of directors and studios under their thumb. From 1911 to 2017, the US government financially sponsored nearly 2,000 movies and televisions show. This collusion has skyrocketed in recent decades, with 900 of those 1100 television shows being created after 2005. The former CIA agent Bob Baer describes this intermingling between Hollywood elites and the US government: "All these people that run studios - they go to Washington, they hang around with senators, they hang around with CIA directors, and everybody's on board." This has been true since the inception of Hollywood.

Hollywood — often dismissed as mere entertainment — is in fact the grand theater of modern myth-making, perpetuating occult archetypes and esoteric narratives that have been deeply imprinted onto the collective consciousness.

As I have previously noted in The Power of Symbols:

With the babelizing of languages seen in Genesis 11, the ancient mysteries and knowledge of the Babylonian rites were dispersed into the myriad cultures of the world. Manley P. Hall, the prolific occult historian and Freemason, expounds on this topic in his magnum opus (emphasis mine):

Symbolism is the language of the Mysteries; in fact it is the language not only of mysticism and philosophy but of all Nature, for every law and power active in universal procedure is manifested to the limited sense perceptions of man through the medium of symbol. Every form existing in the diversified sphere of being is symbolic of the divine activity by which it is produced. By symbols men have ever sought to communicate to each other those thoughts which transcend the limitations of language. Rejecting man-conceived dialects as inadequate and unworthy to perpetuate divine ideas, the Mysteries thus chose symbolism as a far more ingenious and ideal method of preserving their transcendental knowledge. In a single figure a symbol may both reveal and conceal, for to the wise the subject of the symbol is obvious, while to the ignorant the figure remains inscrutable.

— The Secret Teachings of All Ages

To the practitioners of the Mystery rites of Babylon, these symbols serve as a universal language to communicate hidden truths in plain sight. Only the enlightened and the illuminated are privy to the true esoteric meanings of these symbols, the ignorant masses remain oblivious.

The language of cinema is far from neutral: this is especially evident in films steeped in occult imagery, where layers of meaning cater to both the initiated and the unwitting masses.

At the heart of so much medieval, and now modern, occult symbolism lies a deliberate inversion of traditional Christian icons and narratives — not as mere transgressive acts of artistic expression, but as a purposeful statement of rebellion and subversion. The elite filmmakers and cultural architects of the 20th century understood well the potency of these inverted symbols: by drawing upon ancient esoteric traditions — Hermeticism, Kabbalah, Gnosticism — and layering them into modern storytelling, they created a medium that resonates on both a conscious and subconscious level.

To the masses, these symbols might appear as mere decorations, but to those with eyes to see, they reveal these hidden truths.

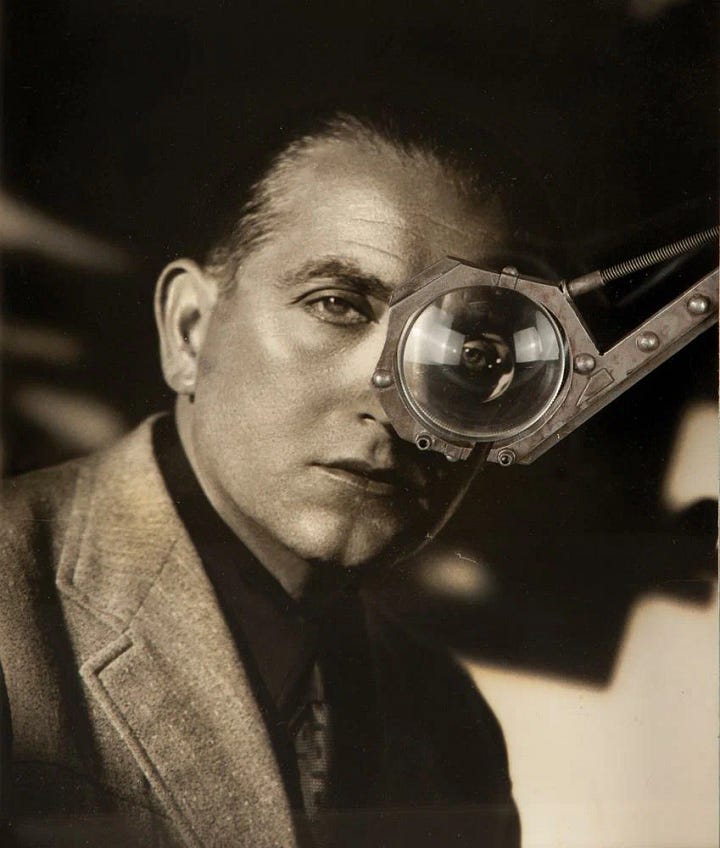

— (L) Fritz Lang, director of Metropolis (1927). (R) Movie poster for Metropolis (1927).

Symbolism too is a tool of manipulation, as it bypasses the intellectual barriers that might otherwise reject the ideas they encode. Through repetition and ritual, cinema inculcates its audience with values and visions that would be unpalatable if delivered explicitly. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) stands as one of the most ambitious and overt examples of this symbolic architecture. Released during a period of immense social and political upheaval in Weimar era Germany, the film offers a vision of technological dystopia that is as much a moral treatise as it is a visual spectacle.

It is no coincidence that Lang’s narrative operates within the framework of occult inversion. The film’s symbols — pyramids, the Whore of Babylon, the all-seeing eye, and androids — are not only laden with meaning but are deployed with the explicit intent to communicate esoteric truths to an elite audience. This audience, unlike the proletariat depicted in the film, is expected to grasp the "hidden wisdom" encoded in these symbols.

The power of Metropolis, therefore, lies not only in its stunning visuals but in its enduring ability to seed the subconscious with an elite cosmology, one in which the masses are perpetually subjugated under the guise of mediation and unity.

“The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart!”

— Maria, Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis has long been the subject of intense analysis, particularly with regard to its use of religious symbolism.

Much of the existing scholarship has focused on the film's visual grandeur, the dichotomy between the upper city and the worker’s underworld, and its heavy handed critique of industrialism. But beneath these readings lies a far more insidious message, one that is directed not at the oppressed, but at the ruling elite. The overt narrative of the film, with its apparent theme of class struggle and the redemption of the worker, is a façade — a strategic misdirection. In this sense, Metropolis does not serve as a cautionary tale for the masses: it functions as a coded warning to the very elite it appears to critique.

Metropolis unfolds in a city divided into two strata: the elite, who dwell in opulent skyscrapers (the New Babel), and the workers, who toil underground to sustain the city’s relentless machinery. The protagonist Freder is the son of the city’s master, Joh Fredersen — a demiurgic figure. His idyllic life in a hedonistic and Elysian dreamscape changes when he encounters Maria, a saintly icon who preaches unity to the oppressed workers. Struck by her beauty and unifying message, Freder descends into the workers’ underworld where he witnesses their plight firsthand.

Meanwhile, Fredersen consults the inventor Rotwang, who reveals his latest creation: a robotic replica of Fredersen’s deceased wife Hel. Fredersen commissions Rotwang to give the robot Maria’s likeness in order to sow discord amongst the workers. The false Maria incites chaos, leading the workers to destroy the machines that sustain the city. Too blinded to even care for their offspring during this tumult, Maria and Freder rescue the children while the workers rage against the machines. In the climactic scenes of the film, Freder mediates between his father and the workers, fulfilling Maria’s prophecy that "the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart."

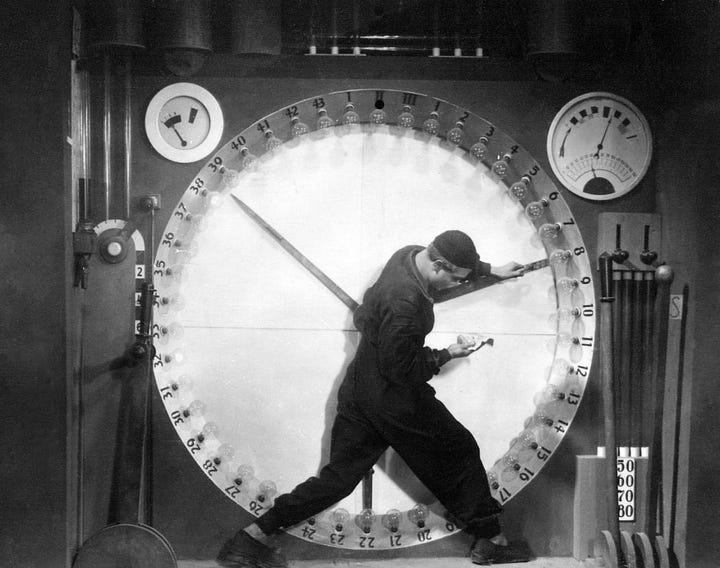

— Scenes from Metropolis (1927).

From its opening shot, Metropolis declares its esoteric ambitions with audacity. The city’s pyramidal skyscrapers, bathed in radiant light, initially evoke notions of progress and enlightenment. Recall that the unfinished pyramid represents the Great Work, an alchemical concept from the Phoenician mystery cults of antiquity. It is a symbol for the perfection of man and his transcendence into immortality through knowledge. Therefore, in this completed pyramid we see the fruition of that goal — Babel reborn.

Yet, as the camera descends, the pyramids dissolve into darkness, an unsettling inversion that encapsulates the Hermetic axiom “As above, so below.” The inversion of light and darkness that opens the film is not accidental, of course: it mirrors the esoteric belief in the necessity of opposites for transformation.

It is the Hegelian dialectic writ large, both in symbolism and narrative structure.

— Scenes from Metropolis (1927).

The light of the so-called elites — the upper city perched above in its gleaming splendor — shines as the workers toil in darkness below. Maria’s underground church, a space seemingly filled with Christian iconography, represents a twisted refuge for the workers. It offers them hope, but a false one. This church, instead of pointing them toward genuine salvation, becomes a place where the workers' need for meaning is channeled into their continued submission. The veneration of Maria here is but a psychological trap — another method of control. The workers are spiritually manipulated to believe they are on the verge of redemption, all while their suffering continues unabated. The subtle anti-Christian message of such a narrative is readily apparent upon a closer examination.

Maria, the film’s spiritual nucleus, is intricately tied to the esoteric tradition of Sophia — the Gnostic figure of divine wisdom. In Gnostic mythology, Sophia bridges the divide between the ineffable Pleroma and the fallen material world. Her role mirrors the false "messiah" figures the elites create: an image of salvation that pacifies the populace without ever leading to true freedom. In this context, Maria’s role isn’t to elevate them spiritually, but to bind them emotionally to a false understanding of their plight. She too is an instrument of control, just not by force.

— Scenes from Metropolis (1927).

Time is another key psychological tool, shaping how the workers perceive their existence. The relentless ticking of clocks and the repetition of work are not merely mechanical — they’re psychological traps. Their lives become a cycle of meaningless repetition, draining their ability to imagine a life beyond servitude. The elites’ control and changing of time is a psychological weapon, thereby disorienting the workers, unable to see beyond their immediate labor.

The scene of the machine-Moloch devouring workers is amongst the most overtly esoteric and allegorical moments in the film. Freder’s hallucination transforms the machine into an altar of Moloch, the ancient Canaanite deity infamous for child sacrifice (a topic I have discussed at length in Saturn, Sabbath, & the Cube, Part I). Here, Moloch becomes a potent symbol of industrialization’s insatiable appetite for human life and dignity. The workers are reduced to offerings in a ritual of modern idolatry.

— Scenes from Metropolis (1927).

— Scenes from Metropolis (1927).

The android Maria is where the true manipulation becomes clear. She doesn’t offer pseudo-salvation, but chaos — a physical manifestation of the system’s dual nature. Rotwang is not merely a practitioner of science — he is a sorcerer, the archetype of the modern occultist who uses technology as a tool of enslavement. His creation of the android Maria is a manifestation of the elite’s true ambition: not to liberate humanity, but to subjugate it through the manipulation of reality.

Her seductive performance later in the film isn’t just about titillating the elite and dysregulating the workers — it’s about breaking their minds and turning their desires into something that serves the system. The workers’ chaos is not a path to liberation: it’s a channeling of their deepest, most primal instincts into a revolt that ultimately leads nowhere, ensuring that they remain trapped in the cycle of destruction and renewal. The film’s psychological depth is revealed here: the workers' rebellion isn't a true revolutionary act, but a way to reassert the control of the elite by manipulating the desires of the workers.

— Scene from Metropolis (1927).

The film’s apocalyptic climax is a psychological revelation: the workers’ rebellion, far from liberating them, only serves to reinforce the system. The destruction of the false Maria is not an act of redemption; it is an act of reformation, bringing the workers back into the fold of the elites' control, albeit temporarily disrupted. The cycle continues, revealing that the workers’ revolt is psychological rather than truly revolutionary. The elites understand that in order to maintain control, they must manipulate the deepest psychological desires of the people — promising them salvation, only to ultimately lead them back into the same system of exploitation.

This rebellion was no true challenge to the system: it is a carefully choreographed dance, a trap laid for them by the very forces they oppose.

“What if one day those in the depths rise up against you?”

— Freder Fredersen, Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis is not merely a film about social struggle, nor is it a naïve critique of industrialization — it is a deliberate esoteric construction, designed to communicate a far darker message.

The real savior in Metropolis is not Maria, but the elites themselves, who wield the power to define the narrative. They have constructed a world where revolt is inevitable, but they ensure that any uprising will be channeled, redirected, and ultimately controlled. The film’s conclusion, in which the workers are pacified by the supposed reconciliation between Freder and Maria, is not a victory for the oppressed. It is a victory for the elites, who know exactly how to maintain control: by manufacturing the illusion of progress, of reform, of change — all while keeping the masses under their thumb.

Like so much of cinema, Metropolis is not a film for the masses, but for the elites. Its central thesis is a warning: the stability of their dominion depends on the careful mediation of tensions between the ruling class and the oppressed. The film’s final message, that "the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart," is not a call for genuine reconciliation but a strategic reminder that controlled opposition is essential. The mediator must bridge the gap, not out of altruism, but to preserve the system’s integrity. The film’s overt narrative is a ruse, meant not to warn the masses but to convey this coded message to its true audience.

The figure of the Whore of Babylon, central to the narrative’s climactic descent into chaos, is not simply an ancient symbol of spiritual degradation — it is a blueprint for the cultural manipulation of the masses. This imagery is not lost on contemporary pop culture, where it has been repurposed by figures like Madonna, Lady Gaga, and Beyoncé. Movies like Batman and Blade Runner intentionally modeled their urban hellscapes after Lang’s. Madonna, in particular, has consciously aligned herself with this archetype.

— References to Metropolis within pop culture are voluminous, from Madonna (L), to Lady GaGa (M) to Beyoncé (R).

Metropolis is far more than a science-fiction epic; it is a modern parable steeped in occult and esoteric symbolism (emphasis mine):

The esoteric idea of the macrocosm replicated in the microcosm, of the hierarchy of worlds, the celestial and the elemental world united through the intermediation of angels and angelic beings is visible first and foremost in the division of Metropolis into three parts: the Brain (where the office of Joh Fredersen is located), the Eternal Gardens (a kind of intermediary heaven, where the Sons’ live) and the lowest, the Workers‘ City. All intellectual activity (design, planning, and administration) is relegated to the central headquarters, the Pleasure Garden functions as a limbo for sensual enjoyment, while the Workers who activate the machines are condemned to a life of toil, devoid both of sensual pleasure and intellectual play…

The pentagram and the significance of number 5 are the esoteric elements that traverse Metropolis. Although the futuristic skyscrapers of Metropolis seem to belong more to the science-fiction tradition, the film is saturated with symbolic and religious meanings.

— Roxana Elena Doncu, Ph.D., An Instance of Esoteric Imagination: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927)

Its vision of technological dystopia and class struggle is a mirror held up to its audience, revealing the mechanisms of control that sustain their world. The film’s visual language borrows heavily from Christian iconography, only to invert it into a dystopian nightmare: Babel has been reforged, time has become a disorienting tyrant, and the redeemer a harbinger of chaos. For the elites, it is both a cautionary tale and a guidebook, a reminder that their dominion relies not on brute force but on the subtle art of mediation and manipulation.

The film’s esoteric and Gnostic elements, far from being mere decoration, are central to its message, ensuring that it remains as relevant today as it was nearly a century ago.

Metropolis is far more than a cinematic masterpiece — it is a cipher, a text written for those with the eyes to decode its symbols.

— Metropolis & the Mysteries, digital art, 2025.

“She is the most perfect and most obedient tool which mankind ever possessed! Tonight you will see her succeed before the upper ten thousand. You will see her dance...”

— Rotwang, Metropolis (1927)

The Wolves Within is a must-read for every believer who refuses to be deceived.

Hit the Tip Jar and help spread the message!

This post contains affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission or affiliate fee for purchases made through these links.

Unlock the mysteries of Biblical cosmology and enrich your faith with some of the top rated Christian reads at BooksOnline.club.

Click the image below and be sure to use promo code SCIPIO for 10% off your order at HeavensHarvest.com: your one stop shop for emergency food, heirloom seeds and survival supplies.

Fritz Lang was a talented film maker early in his career, but not being Talmud-raised Jewish, like Spielberg when he started, limited him. His movies made tons of money; but he was somewhat of a maverick, and had character flaws. So he had to be compromised and controlled (again, like Steven) in order for those who owned movie studios to use his skills, until he could make what they wanted made (think "Schindler's List").

Lang was in the army when he started making short films which eventually got him noticed by Joe May, an Austrian Jew who was considered a pioneer of German cinema. May's influence got Lang hired by Decla Film, owned by one of the most powerful Jews in Germany in the '20's and '30's, Erich Pommer, in 1918. In 1919, Lang married Elisabeth Rosenthal, though it would be brief.

Also in 1919, Lang met Thea von Harbou, a married writer who had come to prominence with her gift for propaganda, and a darling with the Weimars. Not long thereafter, Lang's wife would be found dead in the bathtub of mysterious circumstances involving Lang's WWI revolver. He and von Harbou were actually charged with failure to render aid in Elisabeth's death, charges which were unceremoniously dropped. After von Harbou divorced her husband, actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge, in 1920, she and Lang became a couple, marrying in 1922.

(One would not be out of line if s/he noticed that this same happenstance would come to Steven Spielberg later [in the form of Kate Capshaw]. Cohencidence?)

Thea would stay with Lang during his entire pre-Nazi film output, but in 1933 Fritz divorced her when he caught her in bed with an Indian 17 years her junior. Lang himself was about to leave Germany, as his Jewish cohorts and he knew the bandsaw was near, running to Paris, for a while, and then of course to America, signing with MGM.

Lang would never again have success like his Weimar-era movies. Being partially blind compromised his later films, from eye wounds suffered in WWI. Still, he was not making movies like he did in the '20's for obvious reasons other than losing sight -- a cruel fate for one who displayed his love for the Illuminati so effusively, to be certain.

Fritz Lang was the proto-Kubrick.

I recently watched Metropolis for the first time and was blown away by its complexity, enormity, strange beauty, and pure insanity. I chaulked it up to the unusual Fritz Lang and what must have been the odd nature of the people of the time of its creation and presentation. (I'm Austrian decent and have many memories - my own as well as memories of those who related them to me - of the life and past times in the city of Vienna.)

Your excellent essay put the movie and its motives, which I hadn't given much thought anymore, into perspective for me. Wow, and thank you!