“He that FEARS death loses the joys of life.”

— Jan Hus, Bohemian Reformer & Martyr (1370-1415)

Related Entries

The story of the Bohemian Reformation, or the Hussite Crusades, is a largely unknown yet vitally significant chapter in the annals of Christendom: it would begin with the martyrdom of Jan Hus, a man whose fiery faith and unyielding spirit ignited a revolution that reverberates across time.

Born in 1370 in Husinec, a small village in the Kingdom of Bohemia, Jan Hus is a figure of towering significance in the annals of Christian reformers. While Hus was initially a devoted priest of the Catholic Church, he was heavily influenced by the writings of John Wycliffe, an English theologian and early critic of the sacerdotal priesthood. Wycliffe's emphasis on the primacy of Scripture, the rejection of papal authority, and the condemnation of clerical wealth & corruption resonated deeply with Hus who saw in them a clarion call for a return to the unadulterated teachings of Christ.

Hus' theological beliefs coalesced around several key tenets that set him at odds with the Catholic hierarchy. Central to his doctrine was the conviction that the Bible should be the ultimate authority in matters of faith and practice, a belief that stood in stark contrast to the prevailing view that placed the pope and oral traditions on equal (and some would say superior) footing with Scripture. In regards to papal authority, Hus wrote (emphasis mine):

Neither is the pope the head nor are the cardinals the whole body of the holy, universal, catholic church. For Christ alone is the head of that church. …

To such a low pitch is the clergy come that they hate those who preach often and call Jesus Christ Lord.

— Jan Hus, De Ecclesia (1413)

Hus argued (correctly) that Christ alone is the head of His Church (Colossians 1:18). Jan vehemently opposed the sale of indulgences — a noxious practice that had become a lucrative source of income for the Catholic Church but which he saw as the blatant exploitation of the faithful.

In his preaching, Hus denounced too the moral laxity and secular ambitions of the clergy. He condemned the accumulation of wealth and worldly power by the Church & its leaders, often living in opulence while the laity suffered in poverty. In the Kingdom of Bohemia, some 50% of the land was in the hands of the Catholic Church. His sermons, delivered with passionate eloquence from the pulpit of Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, resonated with the common folk of Bohemia.

— Jan Hus (1370-1415).

The political landscape of the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire during the 14th century was such a tangled web of ambition, corruption, & power struggles that it would make George R.R. Martin blush. This period was marked by the Avignon Papacy, a time in which the papal seat was moved to Avignon, France, from 1309 to 1377. The relocation of the papacy was driven by political machinations and the influence of the French crown, leading to a period commonly referred to as the Babylonian Captivity of the Church. For nearly a century, pontiffs were mere puppets of the French king, far removed from the spiritual and moral authority they were supposed to embody: simony, nepotism, and corruption was rampant amongst the clergy.

The return of the papacy to Rome did not remedy the situation; instead, it spiraled into the Papal Schism of 1378, a period of nearly four decades where multiple claimants to the papal throne — one in Rome and another in Avignon — created a schism that further fractured Christendom. This chaos was the backdrop for the rise of Emperor Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire. Sigismund would reign from 1410 to 1437, aspiring to restore order and unity within the Church and the Empire. His call for the Council of Constance in 1414 was ostensibly aimed at ending the schism in the Catholic Church, but it also served to consolidate his power and curry favor with the ecclesiastical authorities.

— Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel: Truth Prevails, ill. by Alphonse Mucha.

“As for antichrist occupying the papal chair, it is evident that a pope living contrary to Christ, like any other perverted person, is called, by common consent, ANTICHRIST.”

— Jan Hus, Bohemian Reformer & Martyr (1370-1415)

Hus' theological positions were not merely academic or theological: they had profound social and political implications.

The Roman Catholic Church, already reeling from the Papal Schism of 1378, viewed Hus' teachings as a direct threat to its authority and unity; and the Church's response to Hus' burgeoning influence was swift and severe. In 1410, he was excommunicated, and in 1412, he was forbidden from preaching. Undeterred, Hus continued to spread his ideas through his writings, his translation of the Vulgate into Czech, and by means of secret assemblies. His most significant works, such as De Ecclesia (On the Church), articulated his vision of a reformed Church governed by the principles of Scripture and led by clergy who lived according to Christ's ensample. In 1414, Hus was summoned to the Council of Constance under the promise of safe conduct from Emperor Sigismund.

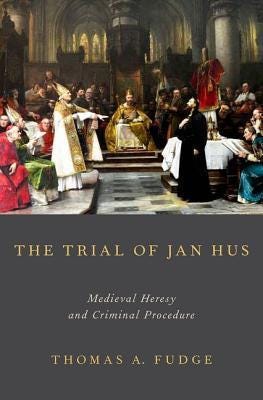

Trusting in this assurance of safety, Hus traveled to Constance to defend himself and his beliefs. However, this was a carefully orchestrated ruse — a premeditated judicial murder. Upon Hus’ arrival, he was immediately arrested and imprisoned by the clerical authorities. The well documented trial that followed was a nothing less than a travesty of justice; marked by bribery, false accusations, and manipulated evidence:

…the accused was placed on an elevated chair for all to see, and we hear judges instructing guards to force the prisoner to maintain silence. The emperor sits in some splendor. A German military governor bears the imperial mace. A Bavarian prince holds the gold crown. A Hungarian knight wields the royal sword. We read of fervent prayers and details of the defendant crying out in despair of justice. There are accusations and arguments. We read of jeers from the men whom the prisoner forgives. We listen as an archbishop mounts the pulpit and delivers a bombastic sermon against the accused, insisting that the body of sin must be eradicated without delay. An old, bald auditor reads the official verdict. When the man who is about to die turns to look at the king, we are told that the embarrassed monarch “blushed deeply and turned red” but never uttered a word. We are brought closely into an emotionally charged scene wherein the defendant is defrocked in an elaborate ceremony of degradation. He holds a chalice, which is taken from his hands as he is cursed and given the moniker Judas. The stole is removed. Then the chasuble. Then the rest of the priestly vestments are stripped from the prisoner. As each item is removed, an appropriate curse is intoned. We find the man weeping, and there are disagreements over how best to obliterate his tonsure. The humiliation continues as the ex-priest is forced to accept an example of the poenae confusibiles and wear a paper miter adorned with demons and bearing letters indicating his crime, while formal maledictions are pronounced by seven bishops over the condemned man.

— Thomas A. Fudge, The Trial of Jan Hus: Medieval Heresy and Criminal Procedure

After months of starvation and physical abuse, Jan Hus was led to the stake on July 6th, 1415. His defrocking was an ornate and calculated act of humiliation, a public spectacle designed to break his spirit and discredit his teachings. Hus, however, remained resolute despite this pillorying, praying for his enemies and forgiving his persecutors. Clad in a paper miter adorned with demons, he was consigned to the flames, dying with a hymn on his lips.

His death galvanized his followers, known as the Hussites, who would carry forward his mission of ecclesiastical and social reform. Jan Hus' martyrdom did not extinguish his ideas, it only fanned the growing fires of reform that would soon engulf all of Bohemia.

— Map of Bohemia and Morovia, 15th century.

In addition to the primacy of Scripture, Hussite theology placed a significant emphasis on the Eucharist and its proper administration. Central to their critique of the Roman Catholic Church was the practice of withholding the fruit of the vine from the laity, offering only the bread during Communion. This practice, known as communion sub una specie, stood in stark contrast to the Hussites' insistence on communion sub utraque specie — receiving both kinds, bread and wine, as instituted by Christ. The Roman Catholic Church's decision to withhold the cup from the laity was seen as a profound corruption and a denial of Christ’s command, representative of a broader pattern of clerical dominance and division between the clergy and the laity. So central was the Eucharist to this movement that the chalice adorning a blood red flag became the symbol of the Hussites.

The Hussites argued that this practice was a grave abuse, fundamentally altering the nature of the sacrament and undermining the communal aspect of the Eucharist. They maintained that both elements — bread and wine — were essential for the complete sacrament. As the Apostle Paul tells us in I Corinthians 11:26 "For as often as ye eat this bread, and drink this cup, ye do shew the Lord's death till he come.” By rejecting these clear prescriptions, the Hussites saw it as yet another manifestation of the broader moral and spiritual decay within the Catholic Church — a symbol of how far the institution had strayed from the apostolic foundations it claims to rest upon.

In response to the judicial murder of Jan Hus, as well as the broader corruption within the Catholic Church, the nobles of Bohemia vowed to interpose themselves between these unjust authorities and the faithful. This commitment was much more than a politically expedient stance, as some have argued: it was an expression of their duty to protect the integrity of The LORD’s Supper and the rights of the laity. In their actions we see embodied what would later be codified in the Magdeburg Confession of 1550 — the Doctrine of the Lesser Magistrates.

The story of Jonathan and David is a profound biblical example of this principle. In 1st Samuel 19:1-7, Jonathan, the son of King Saul, interposed himself to protect David from Saul’s unjust attempts to have him murdered. Jonathan’s loyalty to David and his refusal to carry out his king’s orders exemplify the role of a lesser magistrate in standing up to the higher authority in the name of justice and righteousness. We see also in Acts 5:29 that Peter and the Apostles declare: "We ought to obey God rather than men.” Similarly, Romans 13:1-4 emphasizes the role of governing authorities as diakonos, or servants, of God, appointed to execute justice, restrain evil, and uphold the good. When these authorities fail in their God-given duties; when they become a terror not to evil, but to good, it becomes incumbent upon lesser magistrates to intervene and to obey the highest law and the highest authority — The LORD.

This act of treachery against Hus not only failed to quell the reformist fervor, it ignited a flame that would be carried forward by a man of singular resolve and ingenuity — one of history's most innovative military minds: Jan Žižka.

— Battle of Grunwald (1878), ill. by Jan Matejko.

In the annals of the Christendom, Jan Žižka stands as both a military genius par excellence and a man of unyielding resolve. Born to nobility around 1360 in Trocnov, Bohemia, his early life was steeped in the tumultuous politics of the region: as a mercenary, he honed his skills in the brutal crucible of medieval warfare. His encounters with Hus would profoundly shape his beliefs and the Kingdom of Bohemia.

Despite his defrocking, Hus had served as the confessor to Queen Sophia of Bavaria, the wife of King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia until his imprisonment. As a member of the Bohemian nobility and a seasoned soldier, Žižka also had connections to the royal court. This connection would have provided a context for their paths to cross and for Žižka to be influenced by Hus' teachings.

The murder of Jan Hus in 1415 was a seismic event that shattered the veneer of Sigismund's promises and had exposed the depths of Rome's depravity. Years of tension between the largely German clerics and Czech peasants had exploded into violence. Žižka's reaction to the pending invasion of Bohemia was one of righteous indignation and resolute defiance. The flames that had consumed Hus ignited a fire within Žižka, transforming him from a soldier of fortune to a warrior of the Faith.

His response was not limited to mere words, but action — a call to arms that would reverberate across Bohemia and the centuries to come.

“I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a LION.”

— Alexander the Great

Žižka's tactical genius transformed the Hussite movement from a band of persecuted peasants into a formidable military force that could stand against the might of the Holy Roman Empire and the Papal armies.

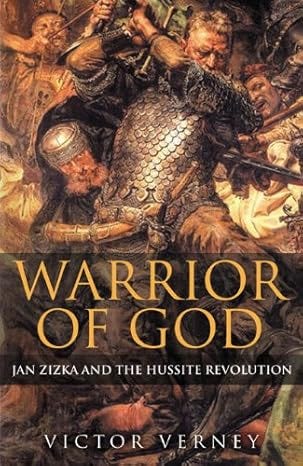

In an era dominated by heavily armored knights and fearsome cavalry charges, Žižka recognized the potential of well-trained infantry units. He developed detailed tactics and innovative formations that leveraged the strengths of infantryman; emphasizing discipline, coordination, and adaptability. Žižka's most famous contribution to military tactics was the development of the wagon fort, or wagenburg (emphasis mine):

Žižka’s battle wagons were built with uniform wheel sizes and axle lengths, perhaps the first instance of mass-produced, standardised military vehicles. The basic body structure was a rectangle of stout planking about a metre high. Hanging planks were suspended from the top of the wagon on one side, functioning like armour. Some wagons had storm-roofs on the top providing additional cover from arrows and other missiles descending at steep angles. Another large hinged plank pierced with firing slits was slung below the wagon body. The wagons were also cleverly fitted with mantlets, or wings, which could be slid out and joined to an adjacent wagon, forming a continuous bulwark. Other movable boards were used to protect the wheels against damage. On the wagon’s inside wall, a ramp was fitted which could be dropped down during battle, allowing crew members quick passage in and out of the wagon. A large container of stones, either attached to the rear or inside the wagon body, provided stability as well as missile ammunition. Several ballast wagons were completely filled with stones and placed at the corners and ‘gates’ of the formation, providing even further stability. The wagon wheels were large and usually iron-rimmed, with the front wheels projecting out slightly in front of the body, permitting them to be chained to the rear wheels of the wagon ahead. With this interlocked structure, the wagons were virtually impossible to manhandle aside or tip over.

— Victor Verney, Warrior of God: Jan Zizka and the Hussite Revolution

These mobile fortresses provided both protection and a stable platform for launching counterattacks from. The wagons could be quickly moved to form new defensive positions, allowing the Hussite forces to adapt to changing battlefield conditions. This method was particularly effective against the heavy cavalry of the German knights who were unaccustomed to such mobile and well-defended positions.

In addition to the wagenburg, Žižka was a pioneer in the use of gunpowder weaponry. Recognizing the potential of early firearms and cannons, he integrated these weapons into his forces with remarkable effectiveness. His troops, armed with primitive handguns and portable artillery, were able to deliver devastating volleys that could break enemy lines and create chaos amongst cavalry charges. The first widespread incorporation of gunpowder weaponry in European warfare marked a significant shift in the balance of power on the battlefield, shattering the dominance of traditional knightly warfare and paving the way for modern infantry & artillery tactics.

Žižka's brilliance extended beyond static defenses and heavy weaponry; he was also a master of guerrilla tactics. In 1423, the Statutes and Military Ordinance of Zizka’s New Brotherhood was released, making it very likely the first infantry training manual ever produced: it was as much a religious tome as it was a manual for warfare. Zizka's edicts mandated unwavering order: no soldier was to advance without permission, fires were only lit by selected individuals, and troops were to pray before every battle. Formation and order were paramount, with booty centralized to prevent greed and ensure fair distribution. His troops were to hold to high moral standards by expelling or punishing the faithless, disobedient, and corrupt.

His familiarity of the Bohemian landscape allowed him to use the terrain to his advantage, executing swift and unpredictable attacks that kept his enemies off balance. Žižka's forces would strike from hidden positions, ambush enemy supply lines, and execute rapid tactical retreats via wagon, only to regroup and strike again. Žižka's contributions to military strategy — particularly his development of the first mobile, combined arms infantry unit; the first infantry manual; his pioneering use of the wagenburg; and his adept utilization of gunnery & guerrilla tactics — underscore his lasting legacy as one of history's greatest military minds.

— Battle of Hussites and Catholic crusaders (15th Century), Jena Codex.

The First Anti-Hussite Crusade was prompted by the radical reforms proposed by the Hussites, encapsulated in the Four Articles of Prague. These articles called for radical changes to the Church’s power structures, including the freedom to preach the Word of God, the right for the laity to partake in both bread and wine during The LORD’s Supper, the renunciation of wealth by the clergy, and the equal punishment of mortal sins amongst all classes by the secular authorities. The challenge posed by these demands to both the ecclesiastical and secular powers led to Pope Martin V calling for a crusade against all of “the Wycliffites, Hussites and all other heretics in Bohemia” in March of 1420.

Emperor Sigismund, driven by political ambition and a desire to bring his recalcitrant subjects to heel, answered the call and mobilized a vast army to subdue the Hussites. The crusading forces, bolstered by knights and soldiers from across the continent, set their sights on Prague — the heart of the Bohemian resistance. Under the leadership of Jan Žižka and other captains, the Hussites were undeterred by the formidable coalition arrayed against them.

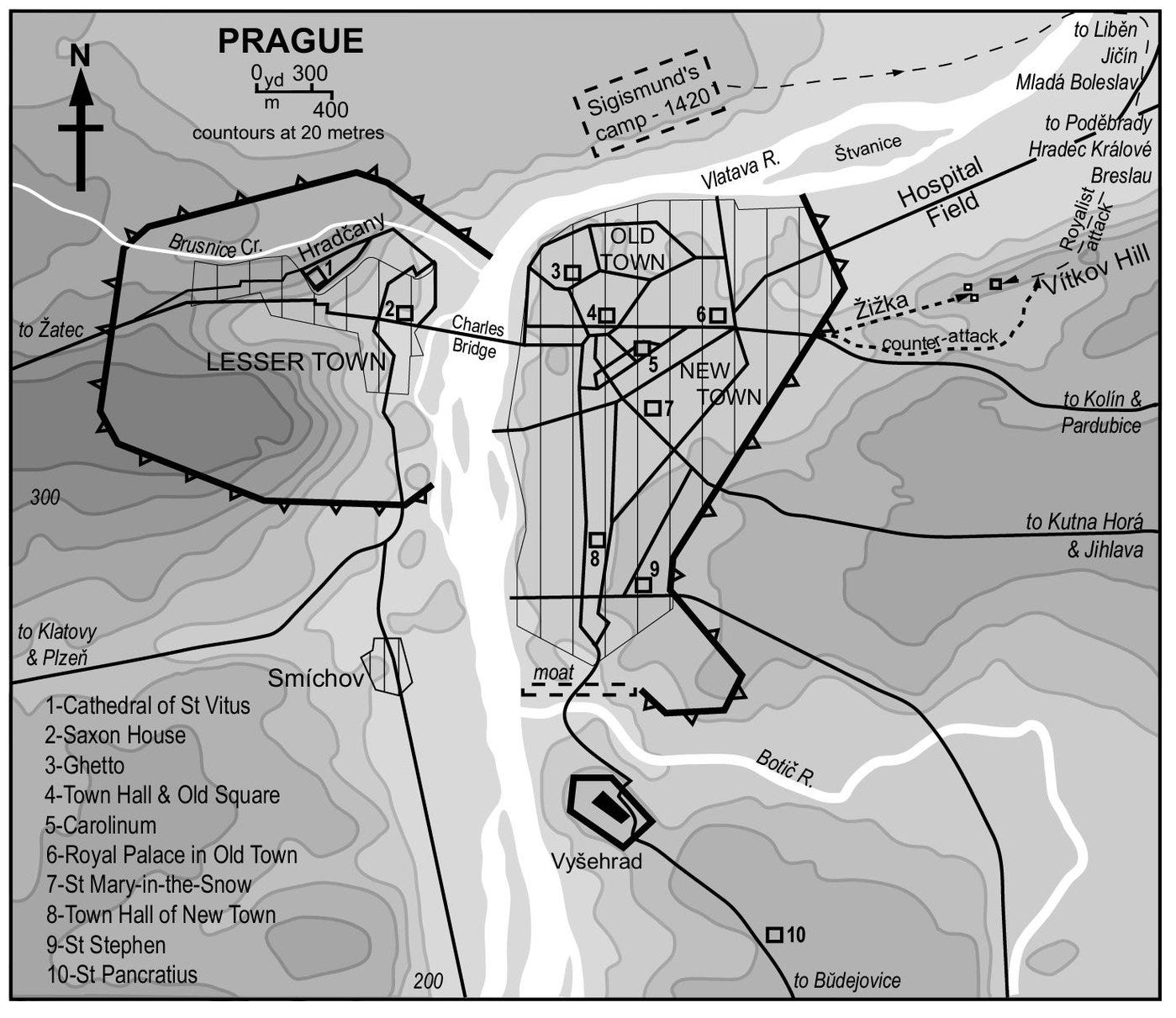

Žižka, by this point both a seasoned campaigner and brilliant tactician, meticulously prepared the defenses of Prague. The city’s fortifications were strengthened, and strategic positions like Vítkov Hill were fortified with war wagons and artillery. As Imperial forces advanced on Prague, the Hussites braced themselves for a siege that would test their resolve and military prowess. Sigismund and his ~80-100,000 strong army began their siege of Prague on June 30th, 1420.

— The Battle of Vítkov Hill, 1420. Source: Warrior of God.

Vítkov Hill overlooks the city of Prague: it would become the crucible where the fate of the Hussite rebellion would be tested.

As the sun rose on the morning of July 14th, 1420, the air was thick with anticipation. Led by Žižka, a small band of 60 or so Hussites had fortified Vítkov Hill with their iconic war wagons; in addition, makeshift towers had been erected to further bolster the line. As a veteran infantryman, Žižka knew the value and power of strategically choosing ones terrain: if Sigismund took Vítkov Hill, Prague would be starved out and her fate would be sealed. The war wagons were chained together, creating an unbreachable fortress bristling with halberds, flails, crossbows, and gunnery.

Austrian cavalry under the command of Heinrech von Isenburg outnumbered Zizka’s garrison roughly 50-1, approaching with the confidence of an assured victory. As the Imperial knights ascended the hill, they were met with a barrage of arrows, bolts, and gunfire. The sound of artillery fire echoed across the landscape, mingling with the shouts of soldiers and the cries of the wounded. The German forces advanced in disciplined ranks, their banners fluttering in the breeze as the terrain forced their columns into ever smaller corridors. The smell of sweat and fear permeated the air as they clambered up the steep incline, their heavy armor clanking with each gallop.

The Hussites, though heavily outnumbered, fought with the ferocity of cornered lions. Žižka’s tactical genius was on full display here; he had positioned his men to exploit the terrain, using the high ground to their advantage. As the enemy approached, Hussite soldiers hidden behind the wagons unleashed a deadly volley of crossbow bolts and gunfire. The initial charge of the Imperial knights was repelled, their ranks thrown into disarray. The hillside was soon littered with fallen men and horses, the smell of blood mingling with the earthy musk of churned soil.

Žižka’s strategic use of the war wagons created further choke points that funneled the attackers into narrow paths, chokepoints where they were picked off one by one. The sound of metal striking metal, the screams of the dying, and the relentless crackle of gunfire filled the air. The defenders, emboldened by their early success, fought with renewed vigor, their chants of “God is our Lord!” rising above the din of battle. The clash was brutal and chaotic; soldiers grappled hand-to-hand, swords clanging against shields, the smell of gunpowder thick in the air.

The Hussites, though weary, held their ground.

— After the Battle of Vítkov Hill: God Represents Truth, Not Power, ill. by by Alphonse Mucha.

As the battle raged on, the sun began to set, casting long shadows across the blood-soaked hill. The attackers pressed inexorably forward, their ranks swelling with each passing hour. Seeing the increasingly desperate situation from the garrison of the New Town, reinforcements emerged to bolster the flagging Hussite force of 30 or so soldiers. These fresh troops made a calculated outflanking maneuver towards Vítkov Hill, threading their way through the vineyards that clung to the southern slope in order to screen their advance.

Caught in the vise of this pincer movement, the knights found themselves wedged between the relentless counter-attack and the steep northern cliff of the hill. The sharp incline was a natural barrier — a fatal choke point. As the knights were herded into this grim trap, their disciplined resolve disintegrated into sheer panic. The Imperial lines broke under the onslaught: soldiers fled in panic, the hillside echoing with their cries of retreat.

The crusaders' rout was swift and catastrophic. In their frantic bid to escape across the river, many knights plunged into the icy waters of the Vltava, their armor dragging them down to their doom. By nightfall, Vítkov Hill was firmly in Hussite hands. The once-confident Imperial army had been shattered, their dead and wounded strewn across the Bohemian countryside.

Žižka's strategic brilliance and the unyielding spirit of his troops had turned what seemed like sure defeat into a resounding victory.

“To most of his contemporaries he was, it seems, not so much an individual character as a great and frightful natural PHENOMENON: a terrific power, sent by God to save the Law of God and to punish the sinners; or, to his enemies, a great scourge of humanity, but even so: sent by God.

That it was God indeed, who made him do what he did, was the firm conviction of Žižka himself.”

— Frederick Heymann, John Žižka and the Hussite Revolution

The Battle of Vítkov Hill was, without a doubt, the most pivotal moment in the Hussite Wars; demonstrating the effectiveness of Žižka’s innovative tactics and the indomitable spirit of the Hussite fighters. It marked the beginning of a series of successful defenses that would cement the Hussites’ reputation as formidable fighters and ensure their place in the pantheon of military history.

Following the triumph at Vítkov Hill, Jan Žižka continued to lead the radical Táborite faction with relentless determination. He secured even more victories, solidifying his reputation as a nigh-invincible infantry commander. Despite losing sight in both eyes in 1421, he remained undefeated in battle until his death in 1424, likely due to the plague. Even in death, his legacy endures, with his tactics influencing European warfare for centuries to come.

Despite fending off four successive crusades, victory would prove fatal to Hussite unity. Following the bitter infighting at Lipany in May of 1434, the radical factions, including the Táborites, were destroyed. This internecine conflict effectively concluded the Hussite Wars, with Sigismund emerging as the principal beneficiary. On August 16th, 1436, he proclaimed peace between Bohemia and the broader Christian world, putting an end to 17 years of war. Wary of further provoking the very people who had ultimately secured his rule, Sigismund delayed his plans to eradicate the Ultraquist movement. His death in September of 1437 thwarted those designs however, allowing the Hussites to solidify their presence, eventually establishing the Reformed Church of Bohemia.

— Sacramenti Sanguinis, digital art, 2024.

The legacy of Jan Hus did not end with the Hussite Wars; it was a seed planted deep in the soil of Christendom, destined to sprout and bear fruit in the form of the Protestant Reformation.

A century after Hus’ martyrdom, Martin Luther would nail his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Church, echoing the calls for reform that Hus had “sealed with his blood” a century before. Luther, like Hus, was a man driven by a fervent belief in the primacy of Scripture and the need to confront the corruption within the Church. At the Leipzig Disputation in 1519, Luther famously declared, “Ja, Ich bin ein Hussite.” Luther's Reformation, much like the Hussite movement, was rooted in the conviction that the Word of God should be accessible to all.

As Luther stood at Leipzig, he realized he was part of that greater narrative, one that transcended his own time and pointed back to the sacrifices and convictions of faithful martyrs like Hus.

Hus’ martyrdom was not the end, but a beginning; a catalyst for change that would transform the very fabric of the Christian faith.

“Ye who are the warriors of God

And of His Law,

Pray for God's help

And believe in Him

So ye will with him always remain victorious.”

— Ktož jsú Boží bojovníci (Ye Are The Warriors of God), Hussite War Hymn

I read a book titled "Doctrine of the Lesser Magistrates" by Matthew J. Trewhella some 10 years back. It was the first time I came across this topic. Pretty good read.

Scipio, first of all a big Helllo to you! I'm currently reading your very good book. I'm interested in learning about freemasonry and its symbols and rituals, which you obviously have studied and understand well. My question is off topic of this post, sorry but I just have to ask, do you still recommend the podcast Firmamental? I listened to it yesterday, podcast date 7/29, with Alex talking to Stephano, a very proud Freemason. Alex did not disagree with anything Stephano said. In fact he was agreeing with him and thought everything he said was very "cool". Wow. Just curious of your thoughts.