Dancing With The Devil: How Sigmund Freud Paved the Way for a Century of Ritual Abuse (Part I)

Examining the issue at its root...

“It is a predisposition of human nature to consider an unpleasant idea untrue, and then it is easy to find arguments against it.”

— Sigmund Freud, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis

Get Scipio’s latest book, The Empire of Lies: the American Empire unmasked.

Hit the Tip Jar and help spread the message!

This post contains affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission or affiliate fee for purchases made through these links.

Unlock the mysteries of Biblical cosmology and enrich your faith with some of the top rated Christian reads at BooksOnline.club.

Click the image below and be sure to use promo code SCIPIO for 10% off your order at HeavensHarvest.com: your one stop shop for emergency food, heirloom seeds and survival supplies.

Related Entries

There are subjects so vile that even the disciplined mind hesitates before confronting them — ritual abuse is one such topic.

By ritual abuse, we mean systematic, often organized, sexual, physical, and psychological abuse within a ceremonial & symbolic framework. Its core aim is not simply domination, nor gratification, but desecration.

Be forewarned: the journey ahead leads us into some of the darkest corners of the human soul. The crimes under examination involve horrific abuse of the innocent, the details of which are both harrowing and stomach churning. Reader discretion is not urged out of sentimentality, but out of respect for the gravity of what will be presented.

Yet, no matter how painful, no matter how uncomfortable, the stories of the victims must be heard. If indeed the accounts of these survivors are true, if indeed the halls of power are rife with such abuse, one struggles to conceive of an issue of more pressing and ethical concern. It is, amongst many reasons, why some of us are unwilling to let the Epstein Affair fade away into obscurity — like so many other state crimes have over the last century.

Since the 1980’s, the pejorative phrase “Satanic Panic” has been used as a thought terminating cliché to dismiss any investigation into systemic ritual abuse. Yet the reports of such acts in the modern era predate this disinformation campaign by decades, and their consistency across continents defies easy dismissal.

One must understand that for many victims of ritual abuse, their memory itself is a battlefield. Their experiences are often clouded by forced drug use, physical torture, and psychological conditioning. A critical factor in the reception of these accounts is that the victims are often children. Additionally, the accounts of abuse frequently include elements that appear fantastical: animals that speak or figures that seem more demonic than human.

Incredulity is the abuser’s first shield. Critics seize upon these details to dismiss the accounts entirely, but the distortions themselves reveal the abuse’s nature: deliberate psychological fragmentation designed to discredit the victim’s own recollection. We will return to the nature and history of this phenomenon in later installments, but it is critical to address from the outset what is arguably the largest hurdle for many to overcome when first exposed to the topic of ritual abuse.

How did the West — supposedly enlightened, supposedly rational — become fertile ground for such horrors to be conceived and perpetuated?

The trail, disturbingly, leads back to the father of modern psychology himself. For in suppressing the truth of his own early discoveries, Sigmund Freud laid the groundwork for a century — and beyond — of ritual abuse.

— Sigmund Freud.

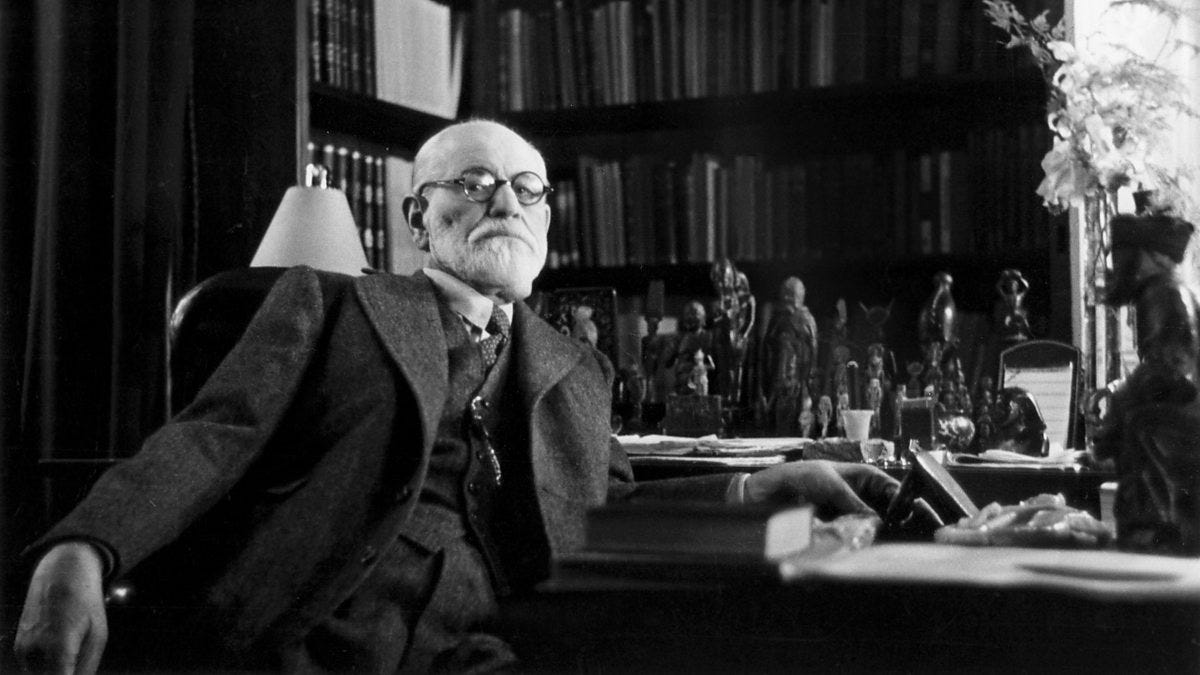

To understand Freud, one must understand the world that made him.

Born to Galician Jews in 1856, Freud was the son of Jakob Freud, a textile merchant in Freiberg, Moravia. Freud inherited not only his father’s Hasidic identity, but a philosophy — a mystical vision that had, by the 19th century, passed through the crucible of the Sabbatean and Frankist “heresies.” Though Sigmund would later apostatize, his relationship with Judaism is a complex one. As Freud scholars Dr. David Bakan and Dr. Joseph Berke document extensively, there can be no doubt that he was deeply influenced by and retained the grammar of that mysticism.

Hasidism absorbed and refined the inner logic of earlier mystical revolutions. As the respected Jewish scholar Gershom Scholem makes clear:

The truth is that it is not always possible to distinguish between the revolutionary and the conservative elements of Hasidism: or rather, Hasidism as a whole is as much a reformation of earlier mysticism as it is more or less the same thing.

— Gershom G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941)

Indeed, Hasidism emerged not as a break from these prior Kabbalistic movements, but as its democratization and intensification — a theology of contradiction.

In this sense, Freud’s atheism was not a revolt against Judaism so much as its modern mutation. Psychoanalysis is, in many ways, a secularized Kabbalah — a point made by Dr. Bakan in his 1958 book, Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition. In more recent years, Dr. Burke has documented Freud’s firsthand knowledge of Kabbalistic texts:

“Freud was familiar with Jewish mystical texts ...He had a meeting with Chaim Bloch, a Lithuanian rabbi and distinguished student of Judaism, Kabbala, and Hasidism.” Bloch translated into German the works of the 16th-17th century Kabbalist Chaim Vital, a leading student of the mystic Rabbi Isaac Luria. When he showed the manuscript of his translation to him, Freud exclaimed, “This is gold!” Moreover, according to Bloch, Freud’s library contained several books on Kabbala in German and French.

— The Secular Kabbalist (The Jerusalem Post, Nov. 29th, 2016)

Lurianic Kabbalah, in particular, frames all of existence in erotic terms (emphasis mine):

At the same time, the Breaking of the Vessels is said to have resulted in a disruption of the flow of divine procreative energy throughout the cosmos, and, particularly, in a disturbance in the normal conjugal relations between the masculine and feminine aspects of the godhead. As a result, much of the divine sexual energy was entrapped in the “husks” of the “Other Side”. [i.e. humans - SE] It is mankind’s divinely appointed task, through proper ethical, spiritual and psychological conduct to discover the kellipot as they manifest themselves in our world, and to free or raise the sparks of light within them (known in Hebrew as Netzotzim), in order that they may return to their proper place as forces serving the divine will. In so doing, mankind is said to liberate the “feminine waters” necessary for the renewed sexual union within God.

— Sanford L. Drob, Ph.D., "This is Gold": Freud, Psychotherapy and the Lurianic Kabbalah

While both grotesque and blasphemous, it reveals something crucial. Jewish mysticism, having reduced the energy of God to what can only be described as sexual urges, made libido the central focus of being. And, indeed, not only is it central, but the free expression of that sexual energy is what is required to “serve the divine will.” In that light, Freud’s conviction that every neurosis was rooted in repressed sexual urges ceases to look like such a novel idea.

In Kabbalist theology, the Cosmos itself is fractured. Humanity’s role is to repair this cosmic disaster through “spiritual labor.” As we have previously cited in Saturn, Sabbath, & The Cube, Part II, despite the death of their false messiah and the conversion of another, the Sabbatean ideology still held deep sway amongst an influential segment of the Jewish elite of Europe (emphasis mine):

Secularist historians, on the other hand, have been at pains to de-emphasize the role of Sabbatianism for a different reason. Not only did most of the families once associated with the Sabbatian movement in Western and Central Europe continue to remain afterward within the Jewish fold, but many of their descendants, particularly in Austria, rose to positions of importance during the 19th century as prominent intellectuals, great financiers, and men of high political connections. …

The “believers” endeavored to marry only among themselves, and a wide network of inter-family relationships was created among the Frankists, even among those who had remained within the Jewish fold. Later Frankism was to a large extent the religion of families who had given their children the appropriate education.

— Gershom Scholem, “The Holiness of Sin,” Commentary Magazine, Vol. 51, No. 1 (January 1971)

By the “appropriate education,” Scholem of course refers to the abominable practices of the Frankist sect — incestous, ritual abuse. Vienna, it is to be noted, was a hotbed for this reprehensible doctrine.

By the 1890’s, Freud had become the physician-philosopher of Vienna’s Jewish intelligentsia. His patients and correspondents were almost all drawn from this same stratum: the Ecksteins, the Bernayses, the Nathansons. The very elite whom Scholem identifies as the inheritors of Frankist “education.” The significance of this fact will bear dramatic consequences upon the burgeoning field of psychoanalytics.

It is against this backdrop that one traces Freud’s entry into B’nai B’rith, the history of which we have covered in a prior series. 1897 is a hinge year for Freud: it marks both the abandonment of the seduction theory and his formal alignment with the Mystery religion:

His subsequent joining of the Vienna B’nai B’rith (in 1897) enabled Freud to clarify the question for himself and find coherent security in his Jewish identity. As Dennis Klein argues, Freud found that his particular Jewish identity could be the vehicle for the expression of his liberal, humanist ideals. Thus, the early period of Freud’s Jewish development moves from naive identification, through ambivalent questioning and distance, to a proud commitment to a Jewishness that expresses humanitarian ideals through a particular Jewish allegiance, defined in both ethnic and intellectual terms. The periodicity of Freud’s Jewish development over the course of his lifetime recapitulates this pattern.

— Moshe Gresser, Sigmund Freud’s Jewish Identity: Evidence from His Correspondence

Historian Peter Loewenberg notes too that Freud “was a loyal member of [B’nai B’rith] and regularly attended its bimonthly meetings.” (Loewenberg, 1970) Freud was, therefore, less the destroyer of Judaism than mystical Judaism’s unconscious heir.

Freud baptized the sexual mysticism of his fathers in the waters of science and called it psychoanalysis.

“The idea of sexual violence in the family was so emotionally charged that the only response it received was irrational distaste.”

― Jeffrey M. Masson, The Assault on Truth

By the mid-1890’s, Freud’s professional path had brought him from the quiet desperation of his Viennese practice to the lecture halls of Paris, where he studied under the legendary Jean-Martin Charcot. There he confronted horrors that his later followers would spend a century denying (emphasis mine):

Freud was exposed to a literature attesting to the reality and indeed the frequency of sexual abuse in early childhood (often occurring within the family); furthermore, in all probability, he witnessed autopsies at the Paris morgue performed on the young victims of such abuse. This was unsuspected by historians of psychoanalysis and consequently any new evaluation of Freud’s stay in Paris must take into account an entirely new body of literature, the importance of which has not been previously recognized.

…when Freud came to evaluate the psychological significance of such acts in 1895 and 1896, it is inevitable that he would think back to the experiences of his Paris days, both his reading and what he witnessed at the morgue.

— Jeffrey Masson, The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory (Ch. 2)

These experiences made an indelible impression upon Freud. Paris had taught him that such crimes were neither myth nor rarity, and that most were committed by relatives intergenerationally.

The data was appalling, but it made sense of what Freud began hearing when he allowed his patients to speak freely. He was amongst the first physicians to believe the victims who told him that something had been done to them: he knew, empirically, that childhood sexual abuse is not fantasy. As a result, Freud published his controversial Seduction Theory in 1896, immediately becoming a professional and social pariah as a result. It was also during this time period that his first interest in B’nai B’rith arose, perhaps as a means of rehabilitating his professional reputation. As Masson notes, “there is no doubt that what Freud meant by a sexual seduction was a real sexual act forced on a young child who in no way desired it or encouraged it.” The ambiguity of that term would be exploited to its fullest extent in the coming years.

— Jeffery Moussaieff Masson, former Projects Director of the Freud Archives.

The story of Freud’s betrayal might have remained buried forever had it not been for one man: Jeffrey Masson, the former Projects Director of the Freud Archives. When he began his work in the early 1980’s, Masson’s task was to edit the Fliess-Freud letters for a new edition. What he discovered ended his career (emphasis mine):

As I was reading through the correspondence and preparing the annotations for the first volume of the series, the Freud-Fliess letters, I began to notice what appeared to be a pattern in the omissions made by Anna Freud in the original, abridged edition. In the letters written after September of 1897 (when Freud was supposed to have given up his “seduction” theory), all the case histories dealing with the sexual seduction of children had been excised. Moreover, every mention of Emma Eckstein, an early patient of Freud’s and Fliess’s, who seemed connected in some way with the seduction theory, had been deleted. I was particularly struck by a section of a letter written in December of 1897 that brought to light two facts previously unknown: Emma Eckstein was herself seeing patients in analysis (presumably under Freud’s supervision); and Freud was inclined to give credence, once again, to the seduction theory.

— Jeffrey M. Masson, Freud and the Seduction Theory (The Atlantic, Feb. 1984 Edition)

The most damning evidence against Freud did not come from his critics, but from his own archives. The Freud family had intentionally edited out the evidence of what Freud originally believed — and why he later renounced it.

The foundation of psychoanalysis — the idea that sexual trauma in childhood is largely an imaginative construct — was born from motivations and pressures that had nothing to do with “science” whatsoever.

It is after this backlash that Freud writes to Wilhelm Fliess — his closest colleague — to defend his theory (emphasis mine):

‘What would you say, by the way, if I told you that my brand-new theory of the early etiology of hysteria was already well known and had been published a hundred times over, though several centuries ago?. . . But why did the devil who took possession of the poor things invariably abuse them sexually and in a loathsome manner? Why are their confessions under torture so like the communications made by my patients in psychological treatment?’

The answer to this question is important, though. Freud did not provide it. For it very much matters whether one says that the reason the devil invariably abuses the witch sexually is that this is a fantasy on the part of the witch, originating in a childhood wish to be possessed by the father, or that the account of abuse is a distorted memory of a real and tragic event that is so painful it can only be recalled by means of this subterfuge. …

A week later, on January 24, 1897, Freud again wrote to Fliess about witches, blood, and sexuality, in a passage (published by Schur) that could only be about Eckstein.

‘Imagine, I obtained a scene about the circumcision of a girl. The cutting off of a piece of the labia minora (which is still shorter today), sucking up the blood, following which the child was given a piece of the skin to eat.’

— Jeffrey M. Masson, Freud and the Seduction Theory (The Atlantic, Feb. 1984 Edition)

Indeed, the answer to this question is of the utmost import. Though Masson proffers only two interpretations, he has left out the most obvious: that Emma Eckstein was ritually abused, as evidenced by the physical signs of mutilation still present on the victim’s body. That this scene was not the hyper-active imagination of a young girl, but testimony that shares striking similarities to the accounts of ritual abuse in today’s literature. (Ritual ingestion of human flesh is one of the oldest documented pagan rites in history, a subject first explored in Black Ops & Black Magic, Part I.)

At the center of this correspondence lies Ms. Eckstein, by some accounts Freud’s first analytic patient. Eckstein came from a powerful Viennese Jewish family, active in both socialist politics and the women’s rights movement. Her treatment coincided with Freud’s most intense period of collaboration with Fliess. An experimental nasal surgery performed by Fliess to cure her hysteria nearly killed Eckstein, and it is during this time that Freud’s disposition towards his patient became increasingly antagonistic. To accept the literal truth of his patient’s stories would have implicated his colleagues, his patrons, perhaps his own social circle.

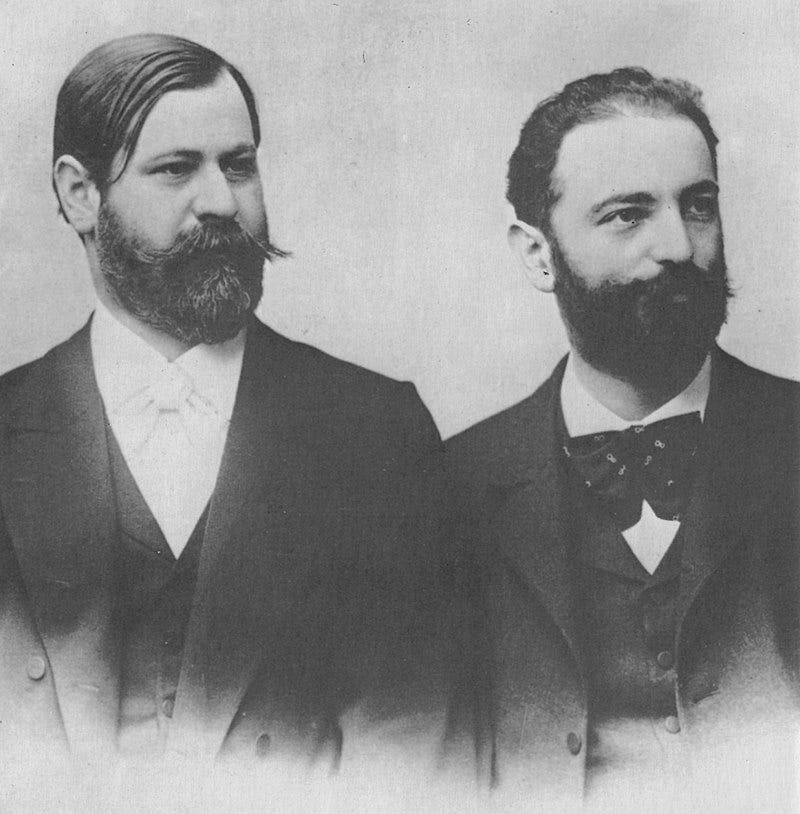

— Sigmund Freud (Left) and Wilhelm Fliess (Right) during the early 1890’s.

In 1897, under social pressure, Fliess amongst them, Freud recanted his theory. He began to speak of infantile wish and fantasy, inventing the now infamous Oedipus Complex. Their letters show Fliess urging him to drop the idea that respectable fathers could be abusers. Freud’s most intimate confidant was the living proof of his theory. Masson notes the bitter irony:

Robert Fliess believed that his father had sexually seduced him when he was a young child. Now, if it is true that Wilhelm Fliess was seducing or otherwise harming his own child at the same time that Sigmund Freud was on the track of his greatest discovery, one that could not be acknowledged in scientific circles or given any theoretical credence (even though it had been mentioned earlier in the French and German medico-legal literature), then we see here one of the poorest matches in the history of intellectual discoveries.

— Jeffrey Masson, The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory (Ch. 4)

Indeed, the pressure to reinterpret the evidence was deeply personal, in more ways than one.

The extent of Fliess’s influence on Freud cannot be overstated. Their relationship was emotional, and likely sexual. The letters between them drip with adoration and jealousy. Freud referred to Fliess as his “second self”: when that attachment soured, he described the experience as “the most traumatic” of his life:

Jones goes on to quote one of Freud’s rare references to his early relationship with Wilhelm Fliess, in a letter to Ferenczi on October 6, 1910:

You not only noticed, but also understood, that I no longer [emphasis in original] have any need to uncover my personality completely, and you correctly traced this back to the traumatic reason for it. Since Fliess’s case, with the overcoming of which you recently saw me occupied, that need has been extinguished. A part of homosexual cathexis has been withdrawn and made use of to enlarge my own ego. I have succeeded where the paranoiac fails.

… By his own telling, it took Freud many years to overcome the hurt he experienced, and he was not about to enter another such relationship with Ferenczi.

— Jeffrey Masson, The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory (Ch. 5)

By his own telling, Freud’s psychic architecture was built on the repression of his own homosexual desires. The irony is grotesque: a man who could not resolve, let alone reveal, his own erotic confusion became the 20th century’s oracle on sexuality. It is no shock that the West has arrived at this place following a man such as that.

If Masson is right — and I think he is — that Fliess was sexually abusing his own children during the very years he was urging Freud to abandon the theory, then the dynamic becomes almost unbearable.

Freud’s retreat was self-protection. To maintain his bond with Fliess, to preserve the fraternity that sustained him, he had to convert crime into fantasy.

“No, our science is no illusion. But an illusion it would be to suppose that what science cannot give us we can get elsewhere.”

— Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion

Freud’s crime is not that he was wrong, but that he knew too much: he stood at the threshold of truth and turned back.

When the Seduction Theory threatened to expose very real crimes amongst the elite — and those within his own social circles — Freud rationalized his findings away. He recast abuse as fantasy, trauma as infantile desire. From that moment forward, Western psychology ceased to be a science and became an instrument of containment.

Even before that point, Freud’s system was never truly science, it was, and is, theology without a god — the Kabbalistic mind turned inward. The Kabbalistic preoccupation with hidden forces, the erotic cosmology of Rabbi Luria, the Frankist theology of transgression — all find their modern form in Freud’s vocabulary of drives, repression, and release.

Psychoanalysis is the Judaizing of the Western psyche.

Freud’s retreat from the reality of abuse was the prototype for an entire civilization’s retreat from moral clarity. Each generation of disciples carried it further. Wilhelm Reich clothed mystical eroticism in Marxist rhetoric and called it liberation. Alfred Kinsey gathered the confessions of predators and called it science. Both believed they were freeing mankind from repression; both were simply extending Freud’s original alchemy — the transformation of perversion into progress.

Freud did not explain the modern world, he helped groom it, and the consequences are everywhere. A century of “liberation” has produced record loneliness and despair. We speak of sex constantly yet understand it less than any generation before us.

Freud’s heirs promised emancipation, the results have been dependence.

Continued in Part II…

— Dancing with the Devil I, digital art, 2025.

“Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.”

— Sigmund Freud

Get Scipio’s latest book, The Empire of Lies: the American Empire unmasked.

Hit the Tip Jar and help spread the message!

This post contains affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission or affiliate fee for purchases made through these links.

Unlock the mysteries of Biblical cosmology and enrich your faith with some of the top rated Christian reads at BooksOnline.club.

Click the image below and be sure to use promo code SCIPIO for 10% off your order at HeavensHarvest.com: your one stop shop for emergency food, heirloom seeds and survival supplies.

Thanks Scipio, I think it is becoming clearer that Freud was propped up by and an asset or agent of the global power structure as an operative to undermine society and the family unit with ideas based on sexual behavior and abuse.

Very good, even brilliant, eye-opening and life-changing essay. Congratulations on writing it. What you have effectively done is to link the Sabbatians/Frankists to the institutional suppression of sexual abuse by way of the harmful choices made by Freud himself. I think this idea is actually true. Freud essentially wanted to preserve his social status and shut down the reality of what was going on. To do that he turned to ideas which had no place in psychoanalysis — bastardizing Kabbalah as so many have. Modern culture lionized Freud and his distortions. How many have suffered because of this cover up? It’s not just sad or frightening, but atrocious. The Frankists may have died out as a cult, but it seems their sick ways became normalized seeped into the larger culture without a rigorous enough examination. This essay is a real contribution to that effort without descending into antisemitism. Bravo.